Why Leading Indicators Failed This Cycle (Or Did They?)

Leading indicators declined for three years with no recession - here is what actually happened.

Traditional Leading Economic Indicators have declined for over 3 years without a recession. This has never happened before.

Understanding why requires revisiting what leading indicators actually are, and why they work.

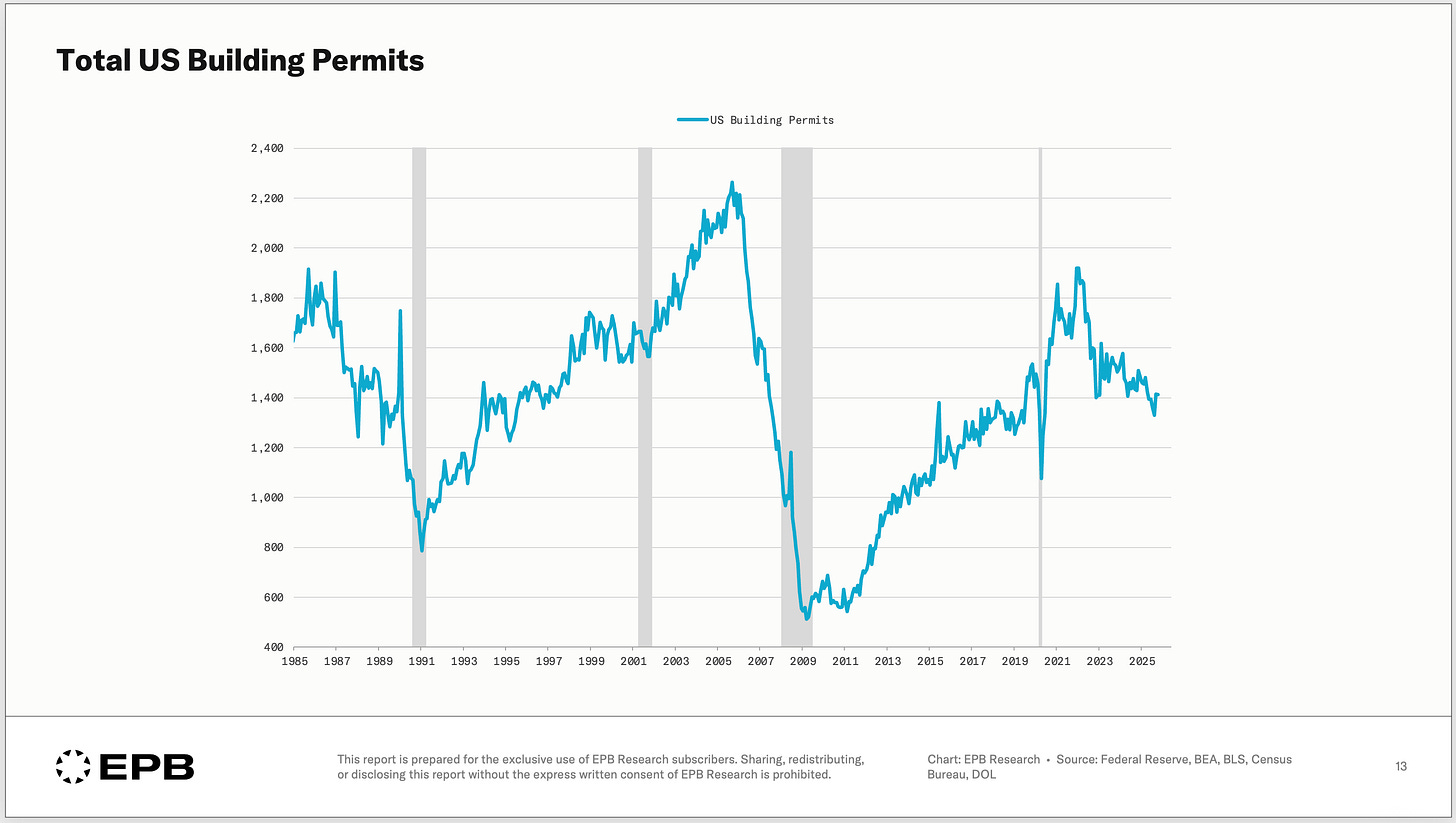

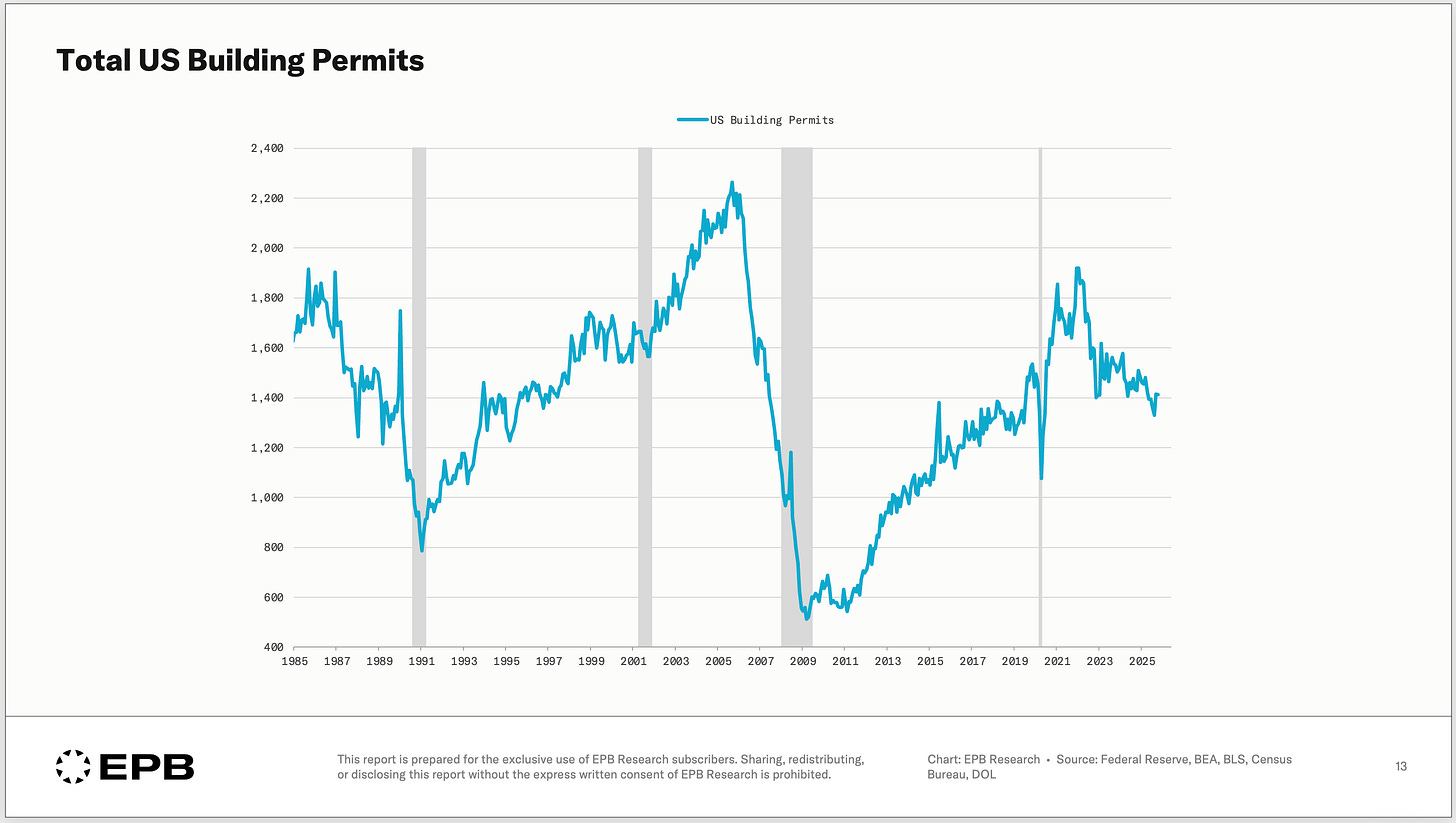

In this post, we’ll use one of the most popular leading indicators, building permits, as a prime example to understand what happened this time and what it means for the validity and usefulness of traditional leading indicators going forward.

What Leading Indicators Are & Why They Work

The economy moves in a sequence. There is a mechanical chain of events that always occurs, and that sequence cannot change. Leading indicators work because they sit at the front of that sequence, measuring the early changes or the early dominoes that fall before the economic changes occur in the later part of the sequence, in data like employment.

Recessions are synonymous with declines in employment. A recession cannot occur without a decline in employment. When leading indicators decline, they are essentially forecasting a decline in employment, although that is several steps away in the normal order of events.

Consider the logic or the normal chain reaction. Businesses don’t hire and fire randomly. They respond to changes in demand or changes in profit margins. But these demand or profit changes don’t appear instantly; they build through a series of steps.

For example, a customer places a new order before a good is produced. Production generally occurs before revenue, and changes in revenue affect corporate staffing decisions. So a decline in new orders forecasts a future decline in employment, but several steps happen along the way that can take an unknown amount of time.

This is why leading indicators have historically worked so well for recession forecasting. They capture the early weakness before it becomes visible in headline employment numbers. By the time unemployment rises, the leading indicators have been declining for months or even years.

But here’s the critical insight that most people miss: leading indicators don’t cause recessions. They measure the front of a sequence that, if completed, produces a recession. The indicator can work perfectly, measuring exactly what it’s supposed to measure, while the sequence itself fails to complete.

That’s precisely what happened this cycle, and we will use the sequence in residential construction to demonstrate this point.

The Incomplete Residential Construction Sequence

Building permits offer the clearest example of what happened during this economic cycle because the sequence or transmission mechanism is well documented, and the failure of the sequence to complete is unambiguous.

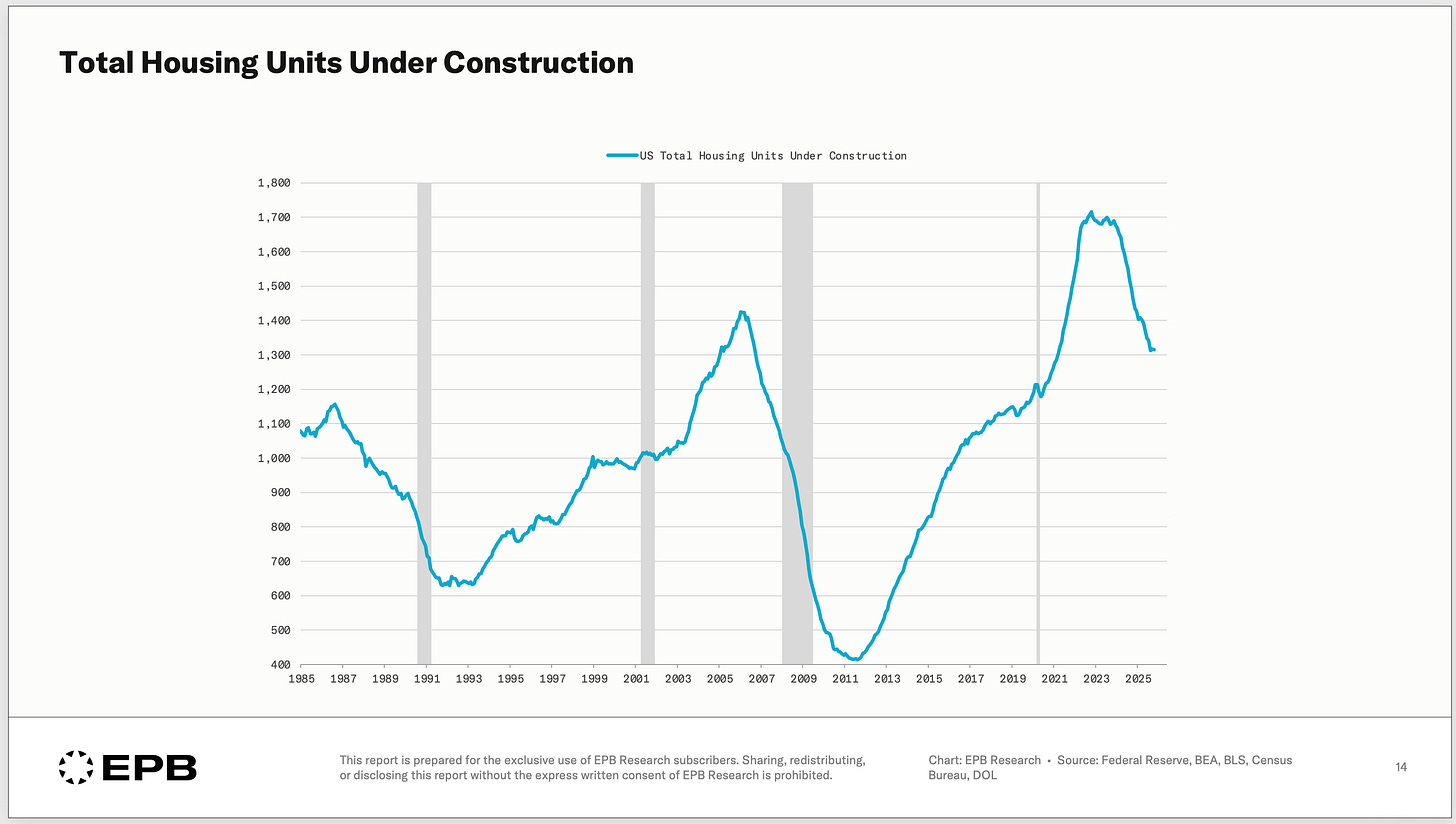

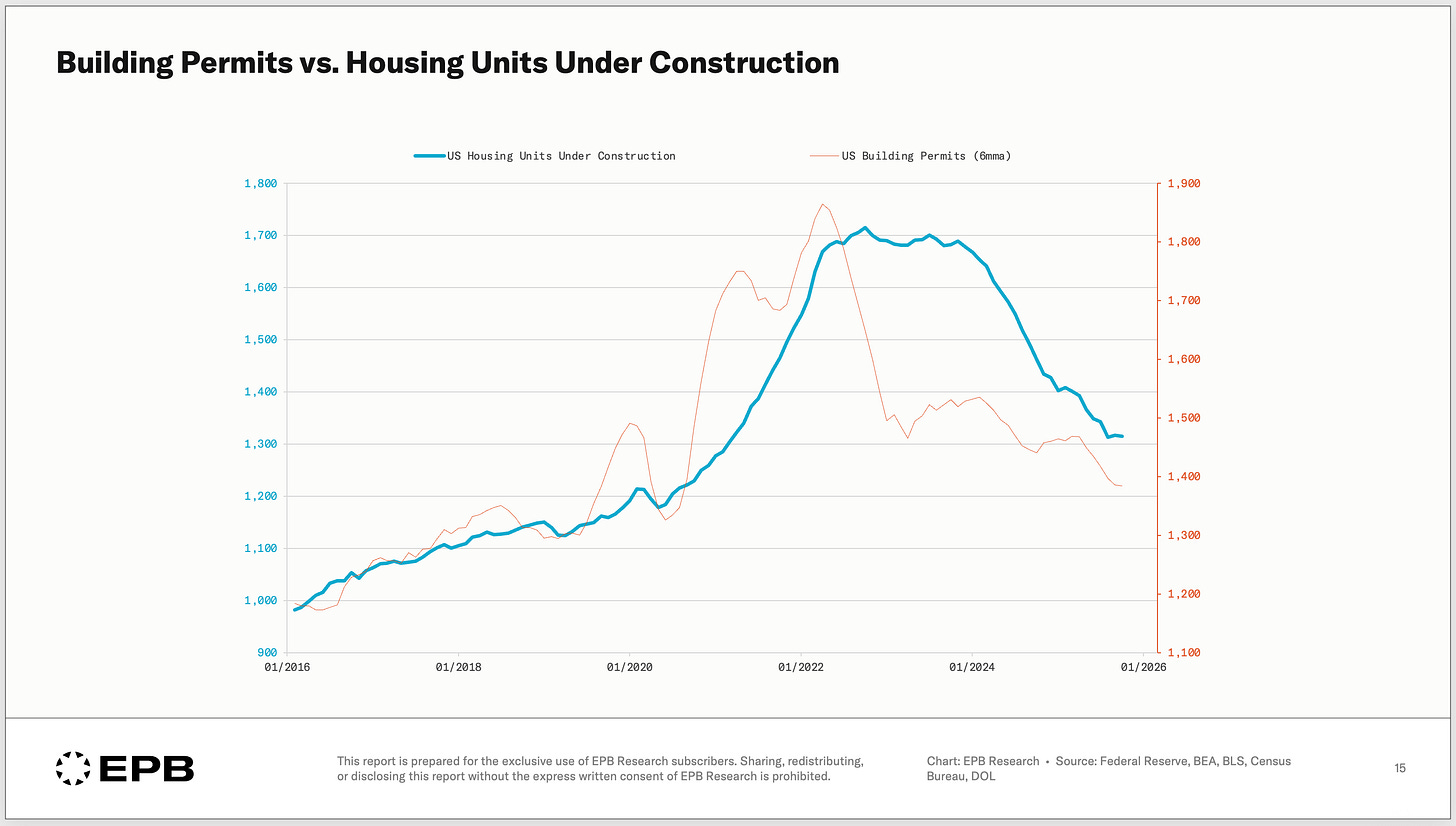

Building permits are issued before construction begins. Building permits signal what residential builders intend to do over the coming months. When building permits decline, fewer homes get started, which means fewer homes are under construction 6-12 months later.

When fewer homes are under construction, there is less demand for employment associated with home construction.

So building permits don’t forecast a recession directly; they forecast changes in residential construction employment, which, given its volatility, drives the vast majority of typical recessionary job losses.

Residential construction and the associated employment are so critical because the sector is highly interest rate-sensitive, meaning changes here occur before other sectors.

A laid-off construction worker cuts back on restaurants, retail purchases, and services. This multiplier effect connects the housing sector to broader consumer spending and, ultimately, to recessionary dynamics.

The sequence, when it completes, looks like this:

Permits fall → housing units under construction decline → residential employment falls → broader labor market weakens → consumer spending slows → recession risk rises.

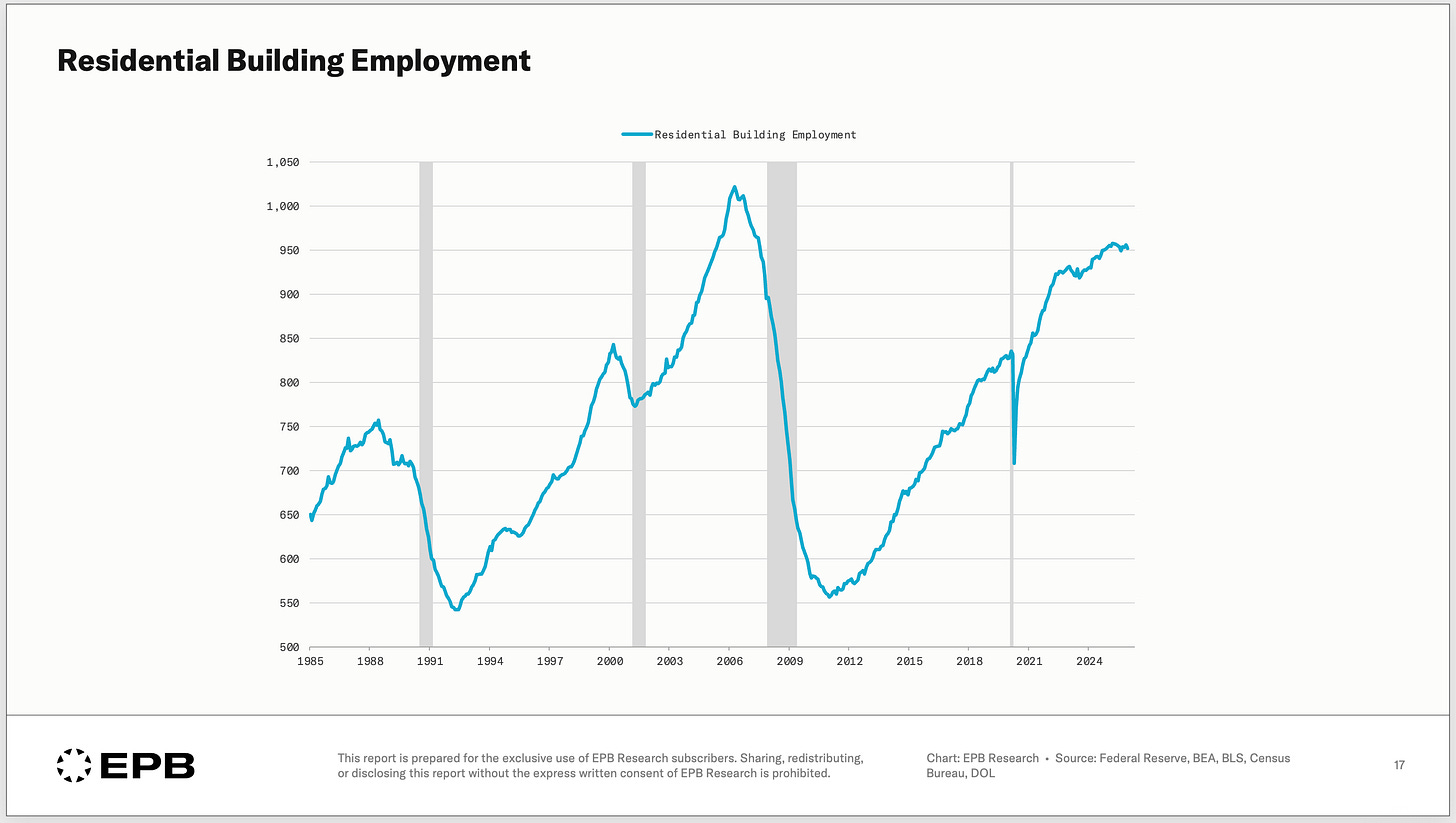

This cycle, the front of the sequence worked exactly as expected. Building permits fell, and then housing units under construction declined. But residential construction employment barely budged. The indicator did its job. The sequence didn’t complete.

Understanding why is essential for forecasting the economy going forward. We need to know if the old relationships or sequence of events have permanently changed or if they have only been temporarily delayed.

The Two Changes That Broke The Sequence

There are two main factors that explain why (so far) the permit-to-employment sequence has failed to complete and thus, failed to produce a traditional recession despite three years of steady declines.

Profit Margins

Residential Remodeling

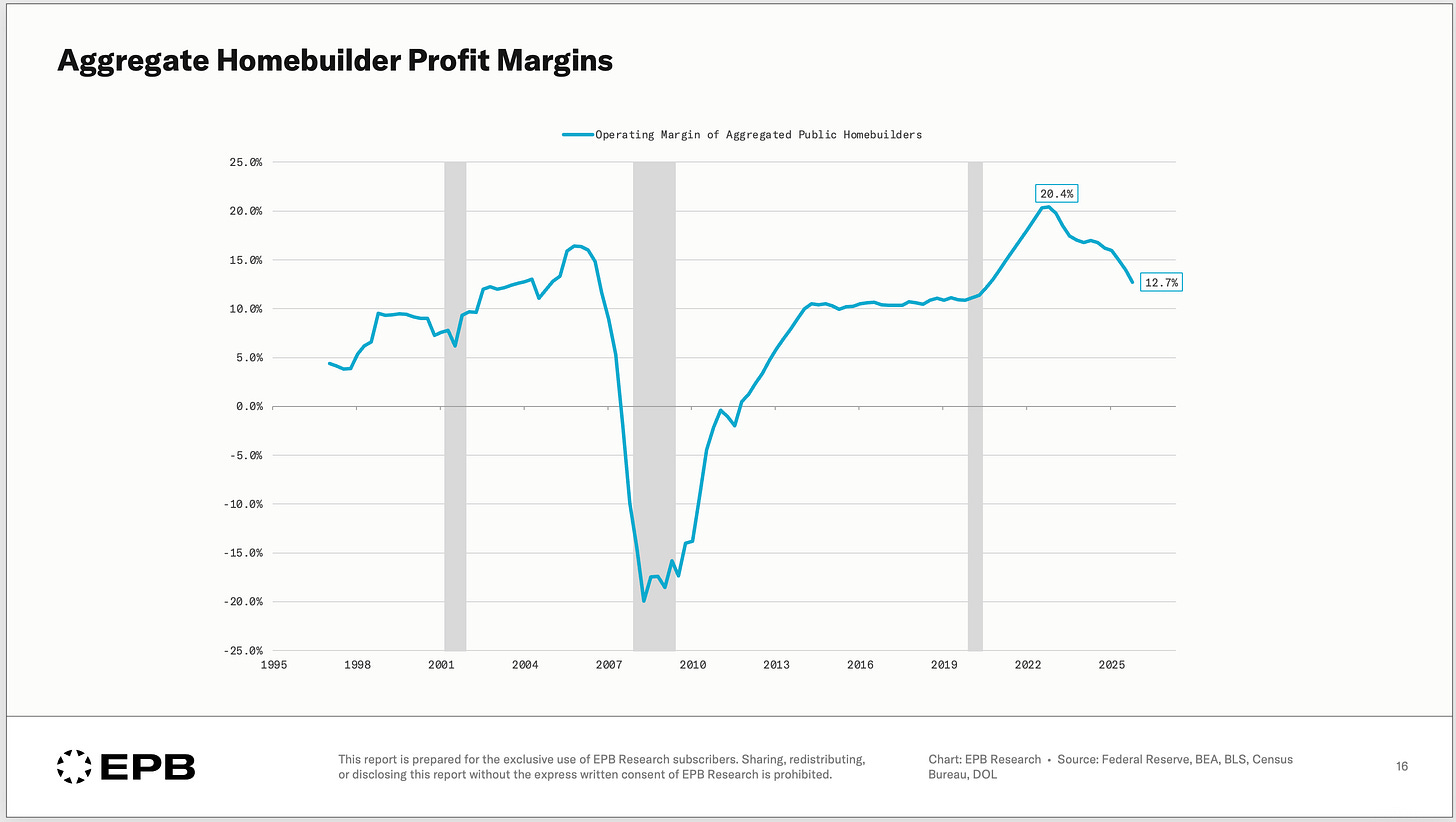

Profit margins in the residential construction sector exploded higher during the pandemic-era boom. Homebuilders, which typically operated with an average 10% operating margin in 2018 and 2019, saw margins explode to 20% as demand vastly exceeded supply.

In early 2022, building permits began to decline as the Federal Reserve raised interest rates. Typically, when permits decline, construction slows, and profit margins compress.

In fact, that’s exactly what happened!

However, profit margins started from such an extreme level, above 20%, that three years of margin compression left builders with an average margin of 12%, still above where they operated for the entire decade pre-2020.

Normally, when construction spending slows, profit margins compress, and that compression triggers layoffs. A builder with thin margins cannot absorb a revenue decline. Costs must be cut, and labor is typically the largest controllable cost.

In this cycle, the margin buffer absorbed the demand slowdown without forcing the employment adjustments that leading indicators had predicted.

Permits declined, construction activity cooled, but profit margins cushioned the blow and have prevented the sequence from fully playing out.

Could the full sequence still occur? Yes.

Margins have been compressing, and if they continue to fall, builders will eventually face the same cost-cutting pressures they always face during downturns.

The question is whether demand stabilizes before margins reach critical levels. If permits and construction spending bottom out while margins remain comfortable, the employment decline never occurs. If permits continue to fall or margins erode further, the classic transmission mechanism could still come into play.

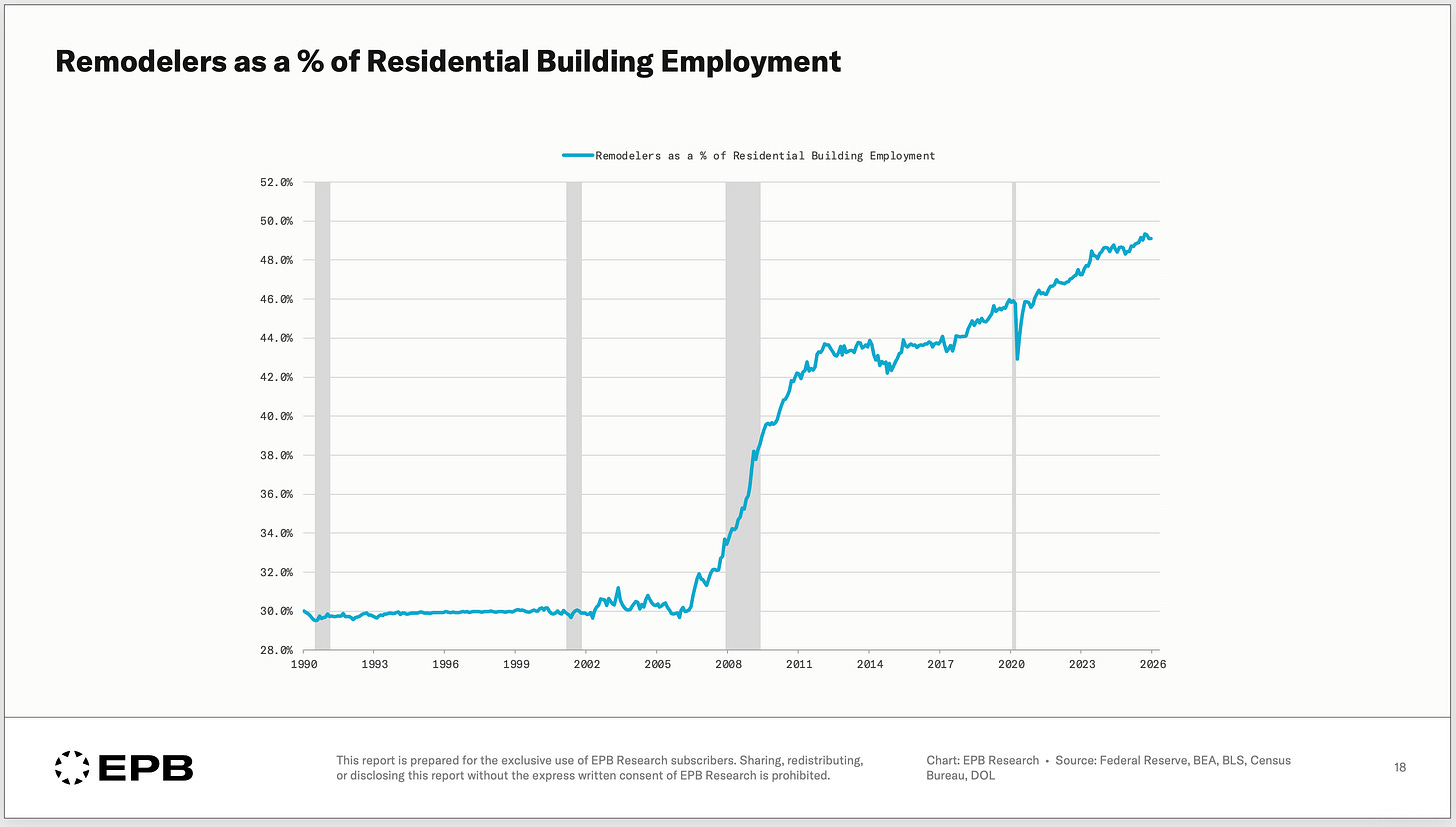

The second factor, remodeling, is more structural in nature.

Building permits track new residential construction. They don't tell us much about remodeling and renovation activity.

Over the past several decades, remodeling has captured a larger share of overall residential construction spending.

This matters because residential remodelers are part of the overall residential building employment sector, which is a big swing factor in the labor market.

In the early 2000s, residential remodelers were only 30% of total residential building employment. Today, remodelers are nearly 50% of total employment.

If we revisit the function of leading indicators, they primarily predict changes in employment, which ultimately drive the recessionary process.

Historically, employment in the residential construction sector was dominated by new construction activity, which building permits accurately forecast. As employment shifted toward remodeling, building permits have less influence on forecasting these employment changes.

The Future of Leading Indicators

This business cycle contained several important lessons regarding leading indicators.

First, the leading indicators don’t predict the recession. The leading indicators are the first mover in a sequence of events that ultimately lead to changes in employment. Following every step of the sequence is extremely important, and jumping from the first to the last step without considering what happens in the middle can lead to mistakes.

Second, leading indicators often measure a subset of economic activity. When that subset's share of the total changes, the indicator's usefulness changes too.

Third, profit margins are an underappreciated variable in the sequence or the transmission mechanism from demand to employment. High margins create resilience. Low margins create fragility. The same demand shock can have wildly different employment effects depending on where margins started.

Where We Stand Now

As of today, the transmission mechanism from building permits to residential employment remains incomplete. The front end worked as expected. Permits fell, and construction activity followed. But the back end, the employment and labor market consequences, never materialized at scale.

The most likely explanations are the combination of remodeling strength and profit margin buffers. Both factors are still operative but potentially eroding. The question going forward is whether economic conditions stabilize before these buffers are exhausted or whether continued pressure eventually completes the sequence that leading indicators predicted three years ago.

This analysis was intended to provide a high-level breakdown of how to track the Business Cycle and its full sequence of events.

Subscribers to our research or consulting services receive updates on the entire Business Cycle Sequence and more granular breakdowns of key themes, such as employment.

Our goal is to help you understand the business cycle, so you are always in a position to make informed decisions with clarity and confidence.

Hi Eric, love your work. One question - a significant majority of residential builds are contract workers (not employees). In other words, no layoffs just no new contracts. Is this reflected in the residential housing employment data?

I don't think you can ignore the off books reduction in the labor supply, associated with the changes in immigration, which will not show up in the data. Additionally, the Fed juicing the economy led to the biggest wealth transfer historically, The top 10% is flush like never before distorting the aggregate. The bottom half is clearly in recession.