Treading Water

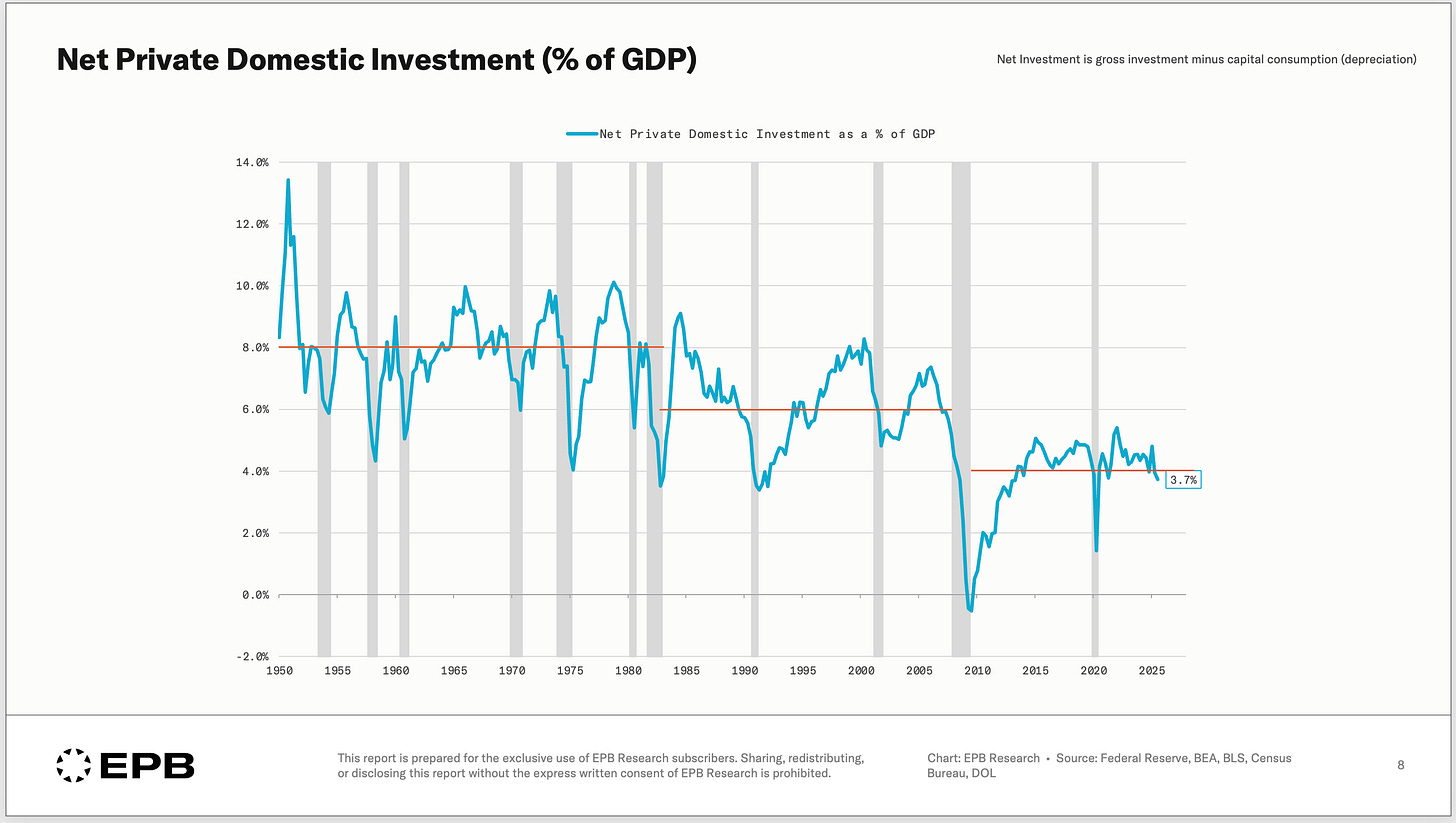

Net private investment has fallen from over 8% to under 4% of GDP over the past several decades. The economy is increasingly just replacing worn-out capital rather than expanding productive capacity.

Net private domestic investment measures how much the U.S. economy is truly adding to its productive capacity each year. Net investment is gross investment minus depreciation. Essentially, it measures if we are expanding our capital stock or just treading water by replacing what has depreciated.

Investment includes residential structures, nonresidential structures, business equipment, and intellectual property.

The answer is increasingly troubling, but it receives little attention because the negative repercussions unfold over years and decades, not months and quarters.

From the 1950s through the early 1980s, net private investment averaged around 8% of GDP. The economy was genuinely building factories, equipment, housing, and infrastructure that would compound productivity for decades. Then it dropped to around 6% through the 1990s. Today, we’re hovering around 3.7%.

A smaller share of GDP is expanding productive capacity. More of what we call “investment” is simply replacing worn-out capital rather than adding new capacity. The decline in structures and equipment is particularly concerning.

Structures constitute the physical backbone of the economy, including factories, commercial buildings, warehouses, power grid infrastructure, mining facilities, and other facilities. These assets have a long life and can serve productivity for decades.

Equipment includes industrial machinery, transportation equipment (trucks, aircraft, rail cars), information processing hardware, medical equipment, and construction machinery.

When net investment in these categories declines, we’re not expanding industrial capacity. Fewer new factories, fewer new warehouses, less physical infrastructure. Workers have less capital and less reliable technology to work with. Machinery ages and becomes less efficient.

Why is this happening? Several factors can explain the secular decline…

The economy has shifted toward intellectual property and software, which depreciate far faster than physical assets. Globalization offshored a lot of capital-intensive manufacturing. An aging population naturally reduces investment intensity. A clear focus on asset prices has redirected capital toward financial engineering and dividend extraction from corporate profits rather than reinvestment in physical capital formation. And larger government budget deficits are crowding out private investment.

The long-term implications are serious. Net investment is the basis of future productivity. Lower investment today means a smaller capital stock tomorrow, and ultimately slower wage growth since real wage improvements are tied to productivity enhancements. In addition, supply constraints emerge more frequently because capacity wasn’t built when needed, and the economy becomes more fragile.

This is the kind of structural problem that doesn’t show up year to year but rather compounds over decades.

The ongoing and growing concern over living standards, affordability, and general economic advancement is all tied to an insufficiency of net investment and worse productivity growth.

Changing this trend will be extremely difficult with large federal budget deficits, a corporate sector that favors dividend extraction from profits over reinvestment, and a low household savings rate due to constraints of expenditure and aggregate profit accounting identities.

But if it doesn’t change, many of our current societal struggles will persist.

This is why the frustration over stagnant real wages isn’t going away. Real wages rise when productivity rises. Productivity rises when workers have more and better capital to work with. And that requires net investment—not just replacing what’s worn out, but genuinely expanding productive capacity.

At 3.7% of GDP, we’re not doing that.

Well…not nearly enough…

Does that 3.7% of GDP figure include private sector AI CAPEX and data centre build out? If so, how much lower would it be sans AI related CAPEX, and if some of that CAPEX turns out to be misallocated, the picture might be even worse than it looks.

Spot-on analysis of the capital formation problem. The shift from 8% to 3.7% net investment as GDP share isn't just a statistic, its a structural decay in how we build future capacity. Watched this play out in manufacturing where companies optimized for quarterly returns over new plant investment, which meant aging equipment and deferred modernization became the baseline. The knock-on effect on productivity and real wages you describe lines up with what actually happened on shop floors over thepast decades.